My fellow radical music educator Jared O’Leary wrote a pretty remarkable paper with a deceptively dry title: A Content Analysis on the Use of the Word ‘Talent’ in the Journal of Research in Music Education, 1953-2012. It got me thinking about talent, and what a pernicious concept it is.

The word talent derives from the Latin word talentum and the Greek word tàlanton, which both mean balance, weight, or sum of money. This sense of the word was the dominant one until quite recently. The use of talent to mean a special natural ability or aptitude derives from a figurative use of the word as referring to money, taken from the parable of the talents in the Bible. Talent has also been used in salacious sexual and underworld contexts; see Jared’s paper for the full etymology.

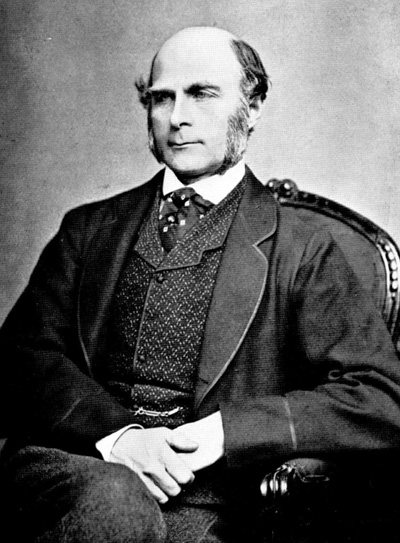

The big question with talent comes down to nature versus nurture. Sir Francis Galton coined the phrase, and he himself believed that “heritable capacities set the upper bound for an individual’s physical and mental achievements that no amount of practice can overcome.” While he recognized that training can enhance your inborn abilities, ultimately it’s futile to fight against your basic nature. Should we believe him? On the one hand, he was a half-cousin of Charles Darwin (you can see it in the forehead.) On the other hand, he also coined the term “eugenics.”

Jared’s survey of the word “talent” in the JRM divides the usages into three categories: talent as nature, talent as nurture, or talent as ability from whatever source. Here’s what he found.

During the first 60 years of publications in the Journal of Research in Music Education there have been nearly 400 uses of the word talent that met the criteria of this study… Of these uses, there appears to be a lack of consensus on the definition of the word. Although the majority of definitions implied the neutral definition of ability, the use of the definition that implied natural abilities was over 30% higher than the definition that implied nurtured abilities. This discrepancy between the word’s usages in music education is problematic.

Problematic is an understatement. The scholarly community of music educators apparently leans toward the assumption that musical talent is innate. But if that’s true, what is the point of music education for everybody? Jared points out that the nature model of talent can be used to restrict access to music to the kids who are already good at it.

If the phrase “your child lacks talent playing the trumpet” is said to a parent (as I have unfortunately heard some music educators and parents say), it could be interpreted as follows: Using the definition of nurture, or the neutral definition of ability, the parent could interpret it as meaning their child has not yet developed the ability to play the trumpet at the expected level and needs to invest more time practicing their instrument. Conversely, using the definition of nature, the parent could interpret it as meaning music lessons would be a waste of time and money because their child does not possess natural talent and therefore will not benefit from studies in music. How that parent understands the definition of talent could have a drastic impact on that child’s music education.

If you base your assumptions on the nurture model, then music becomes a matter of learned expertise, of skills that you develop and knowledge that you acquire. Jared recommends not using “talent” at all, and instead using “expertise” as our standard for measuring musical ability.

A change of terminology could prevent a problematic word from being misinterpreted from its intended use and help eliminate propagation of the false assumption that music is only for those who are born with a natural ability.

I think that he’s absolutely right. First of all, the nature/nurture debate about the origins of musical ability will never be resolved. There are too many confounding variables. Second, even if there is a meaningful “nature” component to musicality, so what? Life experience and enculturation are more than capable of turning the seemingly “untalented” into excellent musicians, and of grinding the musicality out of the seemingly “talented.” Whatever genes there might be in the seed, if it doesn’t fall in fertile soil, you aren’t going to get much of a plant. When you examine stories of supposed child prodigies and natural geniuses (Mozart being the paradigmatic example), you always find a history of rigorous practice and intense education, formal or informal.

As a philosophical matter, we should lean hard toward the nurture view of musical ability. Either it’s the correct one, in which case the nature view is a harmful delusion, or the picture is more complex, in which case erring toward nurture still makes more sense. We want to create an educational culture that values effort and skill acquisition, rather than trying to identify the “innately musical” kids and kicking the rest of them to the curb. Both my research and my observation of little kids teach me that every neurotypical human is born with considerable music cognition abilities, but that those abilities have to be activated by learning. It’s the same with language; nearly everyone has the capacity to talk, but learning how to do it doesn’t happen automatically, it has to be nurtured.

Music education as currently practiced in America has proven itself highly effective at scaring the vast majority of kids away from active music-making. A good step toward fixing this problem would be to disabuse ourselves of the talent myth.